Today we are celebrating Seyi Onabanjo. Since 12 Short Stories started in 2017 we’ve seen many of our writers go on to publish and accomplish great things with their writing. The Prompt to Publication emails are all about celebrating these writers and their wonderful stories.

I hope these interviews will help you and teach you how to use Deadlines for Writers to build your author platform.

Author feature: I’d like to introduce Seyi Onabanjo.

Seyi completed the 12 Short Stories Challenge in 2020 and 2021. He also earned his #braggingrights for The Keep Writing Challenge in 2020.

The video recording of the interview is at the end of this post.

What have you published?

Seyi Onabanjo: Most recently, a short story called “The Weed did not know…” It was published this month, Feb. 2022, by our own Paul Talley & Maria Delaney’s Write My Heart Out “Broken Promises” short story collection

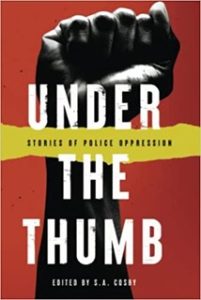

In November 2021, I had a story called “Not Their Type” published in an anthology “Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression,” by Rock and a Hard Place Press, Nov. 2021

I also had a short story “Here, the Mosquitoes are Government Property,” published by the Potomac Review, in Feb. 2012

Has 12 Short Stories helped you as a writer?

Seyi Onabanjo: Most definitely. I think the biggest impact was with gaining access to a like-minded group of people, all trying to improve their craft as writers. I had always struggled with finding consistent, quality critiques of my writing and the 12SS community made a huge difference from my first submission. It’s energizing to find pretty much every genre, expressed in so many styles, and from such different viewpoints. I’ve tried to vary my own writing, in response and mostly, it hasn’t hurt (except for my brief, forgettable attempt at writing romance!)

What did you learn that you applied to your novel?

Seyi Onabanjo: The short story that ended up being published by Rock and a Hard Place Press started life as a 12SS submission. I’d like to think that my dialogue, pacing, and sentence construction have improved since I’ve been a member of 12SS. The editing process with Rock and the Hard Place Press was rigorous but relatively painless as a result.

Did the feedback and discipline help at all?

Seyi Onabanjo: Most definitely. The discipline, particularly with the Keep Writing Challenge of 2020 helped me through that first long COVID lockdown. It also helped me produce 70 stories in 70 days. Some of these short stories ended up in my application to the MA (Creative Writing) program at the University of the Witwatersrand. I am just beginning the second year of this program.

What is your favourite story you wrote for 12SS?

Seyi Onabanjo: “What I wish I said…” I am currently working this story into a novel which I will submit as the thesis requirement of the MA Creative Writing program.

Biography

Oluseyi (‘Ṣeyi) Onabanjo currently lives in New York City, New York, USA.

‘Seyi has an Electrical Engineer degree from the University of Lagos, Nigeria as well as an MBA from Columbia Business School, New York.

‘Ṣeyi worked in corporate IT for many years, but has been most recently employed as a project management consultant, in between bouts of tech entrepreneurship.

‘Ṣeyi is currently completing the MA (Creative Writing) program at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

He is trying to use this experience to release the novel, stuck in him for the past few years. ‘Ṣeyi is prepping for a second hike up (and down) Mount Kilimanjaro, has an extremely patient wife, two ultra-cool kids, multiple bartenders, and hundreds of booksellers partly dependent on him for a living.

Read an excerpt from Seyi‘s story.

Friday at last.

I took my final call standing up and updated the fault log while stooped over the keyboard; car keys close at hand. The office had long emptied. It had taken several attempts before the remote software upgrade took, but the customer’s server was finally up and running.

I didn’t mind working late. In fact, I was beyond grateful that only a year after moving to Lagos, against all odds, I was fulfilling my village teacher’s prediction that I would “become somebody.” I rejected again with a slight shudder the flip side of his prophecy—that I would be the first indigenous principal of my hometown school.

Another letter had been brought to the offices from the village that morning. It sat, travel-stained and swollen with unread demands. I scooped it up and shoved it into my trouser pocket.

***

The night shift operator responded with a nod, which liberated a fresh slick of drool as I waved goodbye. I shook my head and slammed the door, hoping that would keep him awake for a while, then I hurtled down the steps to the parking levels and my pride and joy; a “versatile, fuel-efficient, runabout.”

This bit of marketing propaganda probably worked in 1976. However, a decade and a half of exposure to Lagos’ corrosive sea air and several previous owners had changed her. Now, she’d been reduced to four new-ish tires, a paint scheme that could best be described as postmodern eczema, and not much else. But I didn’t care. She got me from home to work and back again with relative efficiency via my usual haunts. And most importantly, she was mine.

If I’m being honest, I’d admit that her charms were enhanced by one more thing; ownership of a vehicle put me far ahead of all those that had preceded me in the trek from our village to Lagos. Over the past decade or so, the most successful of these fine folk only had the disputed ownership of a battered Vespa to show for their time in the city. But I had a car. I called her Olubankẹ and ignored the office jokes about needing more than God to help me take care of her. The joke was on them, though. She was taking care of me, and she would do so until I could one day afford to trade her for a newer secondhand car.

But to get to Olubankẹ now, I had to navigate the building management guys.

As expected, there were a couple of them hovering around Olubankẹ, their smiles quivering in anticipation. They all seemed to share a single greasy pair of overalls, didn’t have a matching pair of rubber flip-flops between them, and they never missed a chance to shake you down. I unfolded a few low-denomination notes from my left shirt pocket and handed them to the younger of the two. He snatched the money from me and vanished down the closest set of stairs, ignoring my shouts that the funds were for the both of them.

The other chap, probably relatively senior because he was today’s wearer of the shiny overalls, looked at my empty hands. I shrugged at him. He responded with an unpleasant look and a hiss before shuffling off.

I slid behind the wheel and noted the discarded envelopes in the passenger footwell. Crumpled, dirty, my name and work address printed in bold type and even bolder typos, each recalled the envelope I’d shoved into my pocket earlier.

Shortly after taking possession of Olubankẹ, I made the strategic error of driving her to the one church in Lagos frequented by indigenes of my village. I was proud and wanted to show my new status off to old schoolmates and seniors, the parish priest, our resident palm wine tapper, and a host of others. News of my vehicular advancement got home before the end of the service. As a result, I have since received a weekly missive from the village letter-writer. The messages started out requesting, even plaintive but had lately shifted to a more commanding tone.

I was to present the car at my parent’s compound immediately. There, prayers would be prayed, blessings would be blessed, songs would be sung, and drinks would be drunk (at my expense, of course). Only then would me and my car be “safe from all dangers seen or unseen” and “forever protected from the hunger of the road.”

I pulled the letter from my pocket and filed it with the others. My written responses, outlining in vague detail the bureaucracy that was delaying my inter-state driving permit—paperwork that I implied was necessary for me to undertake the drive home— were a work of art. I justified my display of filial disobedience with the mental assertion that Olubankẹ probably wouldn’t survive the trip home.

Seated behind the steering wheel, I thought of that first cold beer and my journey towards it. Our offices are located deep in the city’s armpit, and on most weekdays, the traffic constitutes a test of heat, humidity, stopping, starting, hooting, honking, and plenty of vernacular hand gestures.

And that’s before you’ve exited the ramp from the parking floors

Buy the book

Say their names:

Sandra Bland.

Philando Castile.

Daniel Shaver.

George Floyd.

And too many others.

They died, the victims of a justice system which, for many people in our country and around the world, is seldom just.

In this anthology, our authors explore the darker side of the badge, where a traffic stop can go one of two ways—bad or worse. Where evidence can and will be forged. Where the Blue Wall of Silence closes ranks, and accountability becomes a four-letter word.

At the end, you’ll wonder—is the system broken? Or more chillingly, is it operating just the way it was always intended, and are we meant to live our lives Under the Thumb?

Well done, Seyi!

Want to be featured on Prompt to Publication?

Are you an active, participating member of Deadlines for Writers? Do you have publishing news to share? Please mail mia@12shortstories.com and tell her all about it.